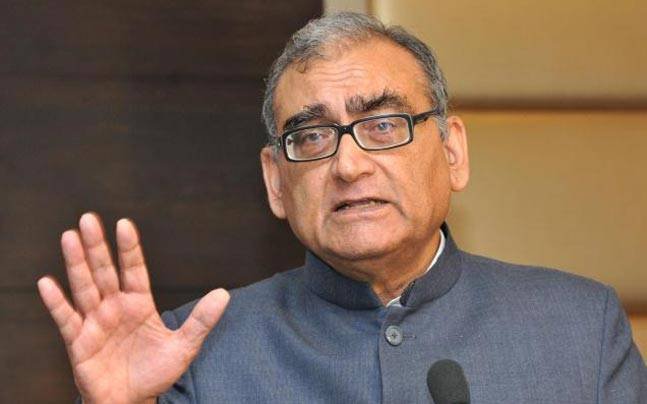

Former Indian Supreme Court Judge Urges Pakistan Supreme Court to Uphold Constitutional Rights in Open Letter

To CJP Qazi Faez Isa and his Companion Judges of the Pakistan Supreme Court Islamabad Dear Brothers/Sisters I regret I have to write this strong letter to you, but I must. You have all taken an oath to uphold the Pakistan Constitution, which has a right to life and liberty ( videContinue Reading