[ad_1]

It’s nearly Beltane, and pagans across the country are getting ready to celebrate. One of the eight festivals in the “wheel of the year”, Beltane is observed from 30 April to 1 May in the northern hemisphere and is an occasion for joyful ritual that marks the moment spring bursts into life, with fires, flower garlands – and perhaps a maypole.

“To be in a circle, to have a huge bel-fire and to jump the ashes into the full summer, it’s very life-enhancing,” says Adrian Rooke, a druid from the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids (OBOD), which runs druidry courses. Annelli Stafford, a practising “eclectic” pagan and the organiser of Beltane at Thornborough Henge in North Yorkshire, agrees: “It’s a really nice start to the year after a long, cold winter.” A regular since 2011, Stafford describes the energy and stunning skies at the three ancient henges, and the event’s welcoming spirit. “There’s a full range from babies to old people with walkers and electric wheelchairs,” she says. The majority of people are pagan, but Wiccans and Christians are also welcome, as well as their four-legged friends: “We’ve had cats, dogs, a bunny, ferrets … everybody’s welcome, as long as you keep your clothes on!”

It’s a similar scene at Butser Ancient Farm’s eclectic Beltane Celtic Fire festival in Hampshire. More pagan-inspired than actual ritual, there’s drumming, Celtic face painting, flower crowns, a May Queen and a Green Man – not to mention a dramatic 40ft wicker man that gets burned at dusk. “It’s a joyful celebration and a collective coming-together, with a decent amount of mead, which is an essential component,” says Kristin Devey, who runs events at Butser.

If you’re thinking that sounds like fun, you’re out of luck for this year. Overnight camping spots for Beltane at Thornborough were booked up weeks ago, and there’s no space left for day visitors. Butser, which has capacity for 2,500 guests, is also completely sold out. “We used to be able to sell tickets on the door,” Devey says. “Now our final release sold out literally in minutes. It was akin to the ‘big festival tickets’ feeling.” That’s a striking degree of enthusiasm for what would once have been considered seriously fringe celebrations.

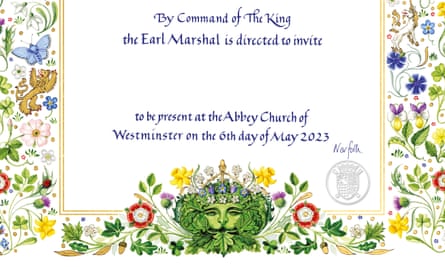

Is paganism, a loosely defined constellation of faiths based on beliefs predating the main world religions, going mainstream? King Charles’s coronation invitation features a prominent image of the Green Man – “an ancient figure from British folklore, symbolic of spring and rebirth”, as the royal website puts it – creating what one paper called a “paganism row” (basically a cross tweet from one member of Mumford & Sons). Thriving fantasy literature and cinema genres are rich in pagan symbolism, and British folk revival musicians frequently draw on pagan inspiration.

While less than half the UK population identified as Christian in the 2022 census, 74,000 people declared they were pagan, an increase of 17,000 since 2011. And that might well be a significant underreporting. When the pre-eminent scholar of British paganism professor Ronald Hutton investigated in the 1990s, he came up with 110,000 – much higher than the contemporary census total. “Most of the pagans with whom I’ve kept in touch do not enter themselves on the census,” he also notes.

Pagan groups report a similar story. “When I joined OBOD 29 years ago,” says Rooke, “there were about 240 people doing the druid course. There are upwards of 30,000 now worldwide and the course is in Dutch, Italian, German …” Heathenry – based on northern European traditions of polytheistic and spirit worship and ancestor veneration – is also “seeing massive growth”, according to Jack Hudson from the “inclusive heathen community” Asatru UK. “When we started in 2013, there were eight of us; now, about 4,000 people have interacted with us over the past 10 years.” Meanwhile, a 2014 survey by the Pew Research Center estimated at least 0.3% of people in the US identified as pagan or Wiccan, which translates to about one million people. That number is expected to triple by 2050.

What is paganism in 2023? For starters, it’s essentially a contemporary creation, drawing on ancient traditions. There were no “card-carrying, self-conscious pagans” from the mid-11th century until the Romantic movement in the 18th century, says Hutton. Although elements endured in Christianity, neopagans only started to establish continuous traditions in the early 20th century. It’s also the broadest of churches, spanning witchcraft, Wicca (the organised witchcraft-based religion founded in the 1950s), shamanism, druidry, heathenry and a vast swathe of non-affiliated “eclectic” pagans. “It has become incredibly mainstream, and that means it’s become incredibly diverse,” says professor of theology Linda Woodhead, who has researched the rise of alternative spiritualities.

One thing that has helped make paganism mainstream is the internet. Finding druids when he first became interested, says Rooke, was near impossible; they were “like the masons – you had to be invited in”. Now the pagan-curious can find information and resources on every sub-variant imaginable online, groups advertise “moots” (meet-ups) and larger gatherings welcome all-comers.

Social media has played a huge part, too. “Witchtok” is huge: the #witch hashtag has 24.1bn views on TikTok (plus 19.1m Instagram posts). “It’s definitely made magic more accessible, 100%,” says Semra Haksever, eclectic witch and owner of the Mama Moon candle and potion shop in east London. “There was always so much secrecy around how you’d meet people and how other people would practise. Now it’s really easy to connect, to learn how to do things. I can’t remember a time when I was connected with so many other women who are into witchcraft.”

Online resources have also enabled a vertiginous rise in “solitary pagans”, or people whose practice is largely private. “Getting pagans to do anything together is like herding cats,” laughs Dr Liz Williams, author of Miracles of Our Own Making, a history of British paganism and co-owner of an online witchcraft shop. “A lot of people feel they don’t want to be told what to do – they’re just happy getting out into nature and doing their own thing.”

The sacredness of nature is one core pagan belief that holds obvious appeal now. As Hutton puts it, paganism fulfils “a need for a spiritualised natural world in a time of ecological crisis”. That resonates: a new literature of wonder, from Katherine May’s Enchantment to Dacher Keltner’s Awe, has articulated our desire for transcendence, rooted in renewed appreciation for a beleaguered natural world. “You’d have to be living in a cave not to be aware of the impact we as human beings are having on the earth,” says Rooke. “A lot of druidry is about preservation, protection, planting trees. It’s ecological, geocentric, idealistic.”

That’s true of heathenry, too: “We are an intensely nature-based religion,” says Hudson. Paganism also speaks to a desire to reconnect with the rhythms of the seasons and the year: visitors to Butser are keen for more events marking festivals of the pagan calendar, according to Devey.

Then there’s paganism’s attitude to women: there are goddesses as well as gods, and there’s the veneration of a sacred feminine. Female empowerment is a particular draw to witchcraft and Wicca. The appeal to young women is obvious, says Williams. “It’s very female-dominated and women-driven in a way which a lot of other patriarchal religions just aren’t.” Pop culture has had a strong influence on waves of uptake, says Williams. “Buffy started off a big interest in Wicca and witchcraft generally. Charmed, before it, had the same effect.” Now there’s Wednesday, the popular Netflix Addams Family spin-off. “I watched a little bit – it’s all about magical young women and it’s got the message that you can be different, so for young women that’s quite a positive message.”

Neopaganism also supports individual freedom and self-actualisation – very contemporary concerns. Hutton describes paganism as “a religion in which deities don’t make rules for humans or monitor their behaviour – humans are encouraged to develop their full potential”.

People often arrive there after a period of spiritual searching and dissatisfaction with other faiths. Rooke became estranged from the intolerant Pentecostal church he joined as a child, journeying through Buddhism and shamanism via a near-death experience (a catastrophic cardiac infection after a botched wisdom-tooth extraction) before alighting on druidry. Heather, a recent druidry convert, became disillusioned with Methodism after discovering reiki healing and moved through spiritualism before becoming pagan. Having spent time quietly observing on the margins of pagan ceremonies at Stanton Drew stone circle, she found the druids “lovely, kind, welcoming people”.

She and her husband organised a pagan handfasting (a wedding ceremony in which partners’ hands are symbolically bound together) and in preparing for that, learned about “the elements, the stones and the land. All these things just fell into place.” Paganism, says Hudson, is “a lot less rigid in terms of worship and practice. It’s not as dominating over your personal life.” That also translates into tolerance. “I think you see each other as souls,” says Heather. “We’re all on our journey.”

That tolerance is not universal. The notion of a deep spiritual attachment to native soil has obvious appeal to white nationalists, and neopaganism has suffered from the far right misappropriating its ideas and symbolism. The Pagan Federation states clearly on its website homepage that far-right ideology is “incompatible with our aims, objectives and values”.

“It’s something our community is extremely aware of,” says Hudson. “We protect our own community by having a strong stance.” Their Introduction to Heathenry document condemns far-right ideology as “simply incompatible with heathenry”. Asatru UK also works with Exit Hate, a charity helping people leave far-right groups.

For Woodhead, what really sets paganism apart isn’t nature or self-actualisation but magic. “The big world religions are very anti-magic.” I wonder whether Williams sees a particular hunger for magic at the moment. “I think it’s perennial, but it is particularly emergent in times of crisis and extreme stress. Unfortunately, most of human history has been a time of crisis and extreme stress!” She says there has been a rise in Ukrainian witchcraft recently, directed against Putin and the Russian invasion. “I guess that is because it’s a last resort: they feel helpless, they’re under terrible threat from a powerful foe and they need to do what they can.”

By contrast, the pagan magic evoked in popular culture is often savage, grotesque and bloodthirsty. Robin Hardy’s film The Wicker Man celebrates its 50th anniversary this year and has become the foundational text of folk horror. In it, a buttoned-up Christian policeman travels to a Hebridean island to investigate the alleged disappearance of a young woman and finds himself confronted by a population in thrall to a pagan cult. Hardy and screenwriter Anthony Shaffer carefully researched the rites and rituals included, from maypole and sword dancing to fire jumping. The film’s ineffable creepiness keeps it at the top of “best horror” lists half a century later, and a long wicker shadow still lies across the whole genre, which is filled with horned, garlanded or animal-disguised initiates, unbridled sexuality and, of course, human sacrifice. The sun-drenched, flower-bedecked bloodbath Midsommar is the obvious example, and last year’s Men, by Alex Garland, also went deep on folk horror tropes, including a Green Man and masked children.

There may never have been a wicker man. The legend emerged from a handful of Roman writings on northern European tribes, according to Hutton. “They’re hostile reports and could indeed be negative propaganda.” Meanwhile, the “enduring tea-towel, film-poster drawing of the druidic wicker man”, he says, comes from a single illustration in a 17th-century book on the history of Britain. Butser’s wicker man, Devey explains, is simply a way for the experimental archaeologists who work there to show off their woodworking prowess: “It’s a Butser craft thing. It’s got no real relation to Beltane or paganism.”

Nor is the maypole a phallic symbol: “Originally it’s a tree covered in flowers and foliage symbolising everything that’s blossoming and sprouting,” says Hutton. No one sacrifices anything except food and drink these days, and what Rooke calls paganism’s “sensuous spirituality” mainly translates to providing a welcoming spiritual home for the whole rainbow of sexual and gender identity and orientation. “There are lots of trans people in OBOD,” he says. “Lots of gay men and lesbian women – it’s very inclusive.” Heathenry also has “a large LGBTQ population that is thriving,” says Hudson.

Paganism in 2023 isn’t a secret front for human sacrifice or a sex cult, nor is it an object of ridicule. If anything, it’s becoming institutionalised. Both Woodhead and Williams compare paganism’s current incarnation to the Church of England. “It’s really quite similar to old-fashioned village Anglicanism,” says Woodhead, citing the Goddess temple in Glastonbury. “They’re licensed to do weddings and funerals, they’ve become like the church of Glastonbury. It’s like the Women’s Institute when you go there.” It’s so well-established that there are now second- and even third-generation pagans, promising a continuity never previously imaginable. Stafford loved meeting the “lockdown babies” when celebrations at Thornborough restarted post-Covid. “It’s nice to see small heathen children running around,” says Hudson.

A representative of a new generation is on the throne now, too, taking on the title of Defender of the Faith among others. King Charles has already expressed his desire to uphold that promise – wouldn’t it be refreshing if he incorporated elements of an ancient-modern, tolerant, open, life-affirming, female-friendly faith into his reign? He’s already passionate about the natural world, there’s that Green Man on the coronation invitation and he almost certainly has a good collection of cloaks. Perhaps it’s time for a pagan king.

[ad_2]

#Dawn #pagans #Everybodys #long #clothes

( With inputs from : www.theguardian.com )