[ad_1]

By all accounts, including his own, David Crosby could be a tricky and difficult character. His career was regularly punctuated by angry arguments, bitter fallings-out, sackings, general discord. Joni Mitchell once waspishly suggested he was “a human-hater”. His former bandmate Roger McGuinn described his behaviour while a member of the Byrds as that of a “little Hitler”. Perhaps the best way to describe him was mercurial. He could be utterly charming and mischievously funny – fans gave him the affectionate nickname the Old Grey Cat – and incredibly generous to other musicians: Mitchell, among others, owed him a great deal. He could also be impossible: overbearing, mouthy, convinced of his own brilliance.

The thing was, he was right: Crosby genuinely was brilliant. He was blessed with a beautiful voice and an uncanny gift for harmony: in the early years, when the nascent Byrds were still blatant Beatles copyists called the Beefeaters, his vocals could make even their weakest material sparkle. He was a fantastic, forward-thinking songwriter. The jazz-influenced Everybody’s Been Burned sounded impressively sophisticated – a cutting-edge example of pop’s increasing maturity – when the Byrds recorded it in 1966. It turned out that Crosby had written it in 1962 while still a struggling folkie. Listening back to the multi-platinum albums of Crosby Stills & Nash (CSN), what’s striking is how original and idiosyncratic his songwriting contributions were.

Yet the Byrds had initially demurred from recording his material: it was hard to find room in among the souped-up folk songs and Dylan covers and the work of the band’s frontman McGuinn and chief songwriter Gene Clark. But almost as soon as Crosby got space on their albums, he changed the band. He forced his fellow Byrds to listen to a collection of Ravi Shankar ragas and John Coltrane’s Africa/Brass over and over again while touring the UK: the two albums inspired the groundbreaking Eight Miles High, widely considered to be the first psychedelic single ever released. He was also the Byrds’ most enthusiastic chronicler of the LSD experience, which informed the frantic I See You and the suitably dazed-sounding What’s Happening?!?! on 1966’s Fifth Dimension.

Emboldened, Crosby didn’t just fight for more room on its follow-up, Younger Than Yesterday, he insisted the band record some of his most adventurous and outre material: not just Everybody’s Been Burned but Mind Gardens, which ventured into freeform territory, “neither rhymed or had rhythm” in Crosby’s words, and, in truth, wobbled a little unsteadily along the line that separates adventurousness from self-indulgence. He successfully lobbied for his song Lady Friend to be released as a single: it was both a flop and a superb song, richly melodic, boasting an intricate brass arrangement and complex vocal harmonies. Crosby performed the latter alone, wiping his bandmates’ contributions and replacing them with his own multi-tracked voice.

That didn’t go down terribly well with the other Byrds, becoming a symbol of increasingly strained relations between Crosby and the rest of the band. The others hated celebrity, remaining surly and taciturn in interviews. Crosby loved fame, rarely missing the opportunity to offer his lengthy thoughts on drugs, politics or free love to journalists or indeed live audiences. Then there was his increasingly domineering attitude in the studio: “I was,” Crosby later said, “a thorough prick.” The band fired him midway through the making of their next album, The Notorious Byrd Brothers, although tellingly they kept his songs: Draft Morning, Tribal Gathering and Dolphin’s Smile were all flatly brilliant, although clearly not brilliant enough for the band to endure his presence any longer.

Crosby seemed uncertain what to do next. He encountered Mitchell performing in a coffee shop and kickstarted her career, helping her land a recording contract and producing her debut album. And he stockpiled new songs, waiting for the opportunity that finally presented itself when the Hollies’ Graham Nash turned up at a house in LA where Crosby and Stephen Stills, formerly of the Buffalo Springfield, were jamming, and added a third harmony to the duo’s vocals.

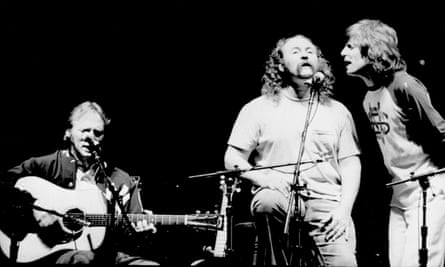

Everything clicked perfectly on CSN’s eponymous 1969 debut. The trio’s harmonies, usually arranged by Crosby, were astonishing. All writers, they had a surfeit of great material: even in such exalted company, Crosby’s Guinnevere, an expansive product of his obsession with finding new tunings for his guitar, stood out. And the album’s sound and mood, relaxed even on rockier tracks such as Crosby’s Long Time Gone, fitted the moment: music to soothe listeners as the 60s party drew to a messy conclusion. It was a huge hit, establishing CSN as the premier example of that most late 60s of concepts, the supergroup. But there were issues. Relations in the band could be volatile, a state of affairs not much helped by their increasing enthusiasm for cocaine. They became more volatile still when Stills’ brilliant but erratic former Buffalo Springfield bandmate Neil Young joined, and Crosby’s girlfriend Christine Hinton was killed in a car accident: Nash opined that Crosby was “never the same” after identifying her body.

Still, for a while at least, the music continued to flow from him. Not just Crosby Stills Nash & Young’s (CSNY) multi-platinum album Déjà Vu – home to Crosby’s twitchily paranoid Almost Cut My Hair – but the frankly extraordinary 1971 solo album, If I Could Only Remember My Name: haunting, richly atmospheric, the vocals frequently wordless and, on closer I’d Swear There Was Somebody Here, authentically unsettling, it might be the fullest expression of Crosby’s restless sense of adventure.

Said adventurousness was there again on 1972’s Graham Nash David Crosby, recorded by the duo when CSNY proved incapable of holding together long enough to follow-up to Déjà Vu. The album’s poppier material was Nash’s work, while Crosby came up with more expansive and exploratory exercises in mood and atmosphere of which Games was a particularly great example. The duo would reconvene, making the beautiful Wind on the Water, after CSNY’s famously turbulent 1974 tour came to a premature conclusion. The quartet had been lured back together by the prospect of making vast sums of money, although the omens were there – they had already tried and failed to record a new album. Proceedings swiftly degenerated into a bacchanal of coked-out excess and off-key vocals that Crosby dubbed “the doom tour”.

But things were even more doom-laden than Crosby thought, or the sunlit tone of Wind on the Water suggested. His increasing addiction – he moved from snorting cocaine to freebasing and using heroin – began to affect his writing, at least in terms of quantity. A man who had battled the Byrds to get as many of his songs as possible on their albums managed only three compositions on 1977’s CSN, an album that sold 6m copies: if the sense of exploratory magic that sparkled throughout Crosby Stills and Nash’s debut had been replaced by solid professionalism, its sound fitted neatly with that year’s vogue for smooth, Californian rock (tellingly, it was at No 2 in the US charts when Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours was at No 1). Thereafter, he stopped writing almost entirely. He cobbled together a solo album from unreleased songs he had written in the 70s. Rejected by his record label, it nevertheless provided the source for his solitary contribution to CSN’s next album, 1982’s Daylight Again: that the implausibly lovely Delta was one of its scattered highlights only underlined the talent that Crosby seemed intent on throwing away.

Just how intent he was is laid out in his 1988 autobiography Long Time Gone, a book that spares few details in documenting his descent: the open sores that covered his face and body, the squalid conditions in which he and partner, Jan Dance, lived, the crowd of dealers and fellow addicts he surrounded himself with – so sinister that even the musicians still willing to work with him dubbed them “the Manson Family” – the endless string of drug and firearms busts. At one juncture, Crosby had a drug-induced seizure while driving a car at 65 miles an hour. At another, Dance was held hostage by a dealer to whom Crosby owed money while he was out on the road. His addiction was such that he refused to let go of his freebase pipe even when a policeman was arresting him backstage. Nash began publicly expressing the view that Crosby was going to die; Young responded to his plight with the scathing Hippie Dream, a song that depicted Crosby in his ruin, “capsized in excess”. His deterioration was made very publicly visible during a chaotic CSNY performance at Live Aid. Running unsteadily through their brief set, Crosby looked decades older than his fellow musicians. “A 14-year addiction to heroin and cocaine has left David Crosby looking like a Bowery bum,” wrote Spin magazine.

Backstage at Live Aid, Young had suggested he would consent to a new CSNY album if Crosby cleaned up. After Crosby emerged from a nine-month stretch in prison on drugs and weapons charges – a sentence that almost undoubtedly saved his life – Young proved true to his word. Soulless and stilted, American Dream was a largely awful album – Compass, which Crosby had written in prison, was a rare highlight among a dearth of decent material – and, if anything, the subsequent CSNY album Live It Up was even worse, a hopeless attempt to marry their harmonies to the booming drums and glossy synth production that was still mainstream US rock’s default setting. It was a problem that also afflicted his post-prison solo albums Oh Yes I Can and Thousand Roads, although anyone prepared to dig deep would find a scattering of songs suggesting his skills were undiminished – the reflective and rueful Tracks in the Dust, the wordless Flying Man on the former, the Mitchell co-write Yvette in English on the latter. And, as Crosby put it: “I was just glad to be there at all.”

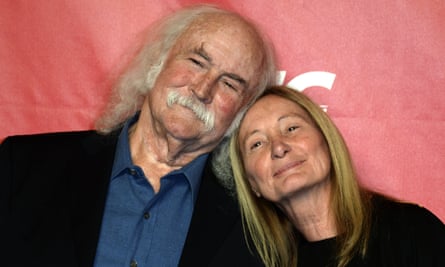

Meanwhile, CSN remained a huge live draw – even more so when Young could be inveigled to join them – while Crosby’s solo career began to blossom. He formed the jazzy trio CPR with James Raymond, who had only found out he was Crosby’s son when he was 30. Raymond also worked on his father’s strong 2014 solo album Croz. Mischievous as ever, Crosby was an enthusiastic participant in CSNY’s confrontational 2006 Freedom of Speech tour, its setlist weighted in favour of Young’s recent Living With War, an album that protested against the George Bush administration and the conflict in Iraq. Their performances provoked boos and walk-outs from conservative fans, but Crosby remained gleefully unrepentant: “Who are these people who come to a CSNY show and complain that we’re political?”

Age and sobriety didn’t diminish Crosby’s capacity to cause trouble. A projected CSN album with Rick Rubin had to be abandoned because Rubin couldn’t get along with him. Next, he fell out very publicly with both Young and Nash – he criticised both for leaving their wives for younger women – which brought both CSN and CSNY to a permanent conclusion. Crosby occasionally expressed regret, but in reality seemed energised by the finality of their split.

Certainly there was a noticeable upswing in the quality of his music. Recorded with much younger musicians, 2018’s Here If You Listen was the best and certainly the most consistent album Crosby had made since the early 70s. On its opener Glory or the poignant Your Own Ride (“I’ve been thinking about dying, how to do it well,” sang Crosby, who was plagued by ill health) it suggested an artist enjoying an unexpected creative Indian summer, an impression underlined by last year’s Live at the Capitol Theatre, which melded CSN classics, songs from If I Could Only Remember My Name and more recent material into an impressive summation of his career.

He also became an enthusiastic user of Twitter – he was still tweeting the day before he died – on which he was variously funny, provocative, infuriating, generous, wilfully argumentative, clearly obsessed with music, and never above reminding the world of his own talent. He was still tweeting right up to his death: his anger about US politics and the environment, praise for photographs of particularly well-rolled joints, approving retweets of fans praising his music – and of an old quote from his former bandmate Stills, a final moment of consensus about their motivation: “The joy of making a wonderful noise together.”

[ad_2]

#David #Crosby #maddening #musical #genius #thrived #chaos #Alexis #Petridis

( With inputs from : www.theguardian.com )