[ad_1]

Smokey Robinson’s first collection of new songs in 14 years is gorgeous, tender and utterly filthy – a concept album about sex called Gasms. Robinson, 83, admits he thought the title would be good for business. “When people think of gasms, they think of orgasms first and foremost … I tell everybody: ‘Whatever your gasm is, that’s exactly what I’m talking about.’” He bursts out laughing. Within seconds of meeting him, you can tell this is a man who’s done a hell of a lot of laughing, loving and living.

On the title track, Robinson sings about eyegasms, eargasms, the whole gamut of gasms. If there is any danger of missing the point, he throws in double entendres that verge on the single. He sings with the silky falsetto of yesteryear, the words perfectly phrased as ever. The album ranges from the exultant (“We’re each other’s ecstasy”) on Roll Around to the biological (“If you got an inner vacancy / Baby, then make it a place for me”) on I Fit in There.

It’s important for him to show that older people are still sexual beings, he says. “When I hear of grandfathers and grandmothers who are 60 years old being talked about as if you’re counting them out and putting them out to pasture, I think it’s ridiculous. This is a new era of life. I feel 50.” He has no intention of turning into an old man, whatever his age.

Has his attitude towards sex changed since he was a teenager? “I still feel the same way, only I’m wiser with it. When you’re young and you have those exploratory feelings about sex, you haven’t lived long enough to know the value of it. So yes, I have a different attitude to it, but I still feel sexual. And I hope I’ll always feel like that. OK, chronologically, I’m 83, but it’s not really my age.”

We are chatting on a video call. Robinson lives in Los Angeles with his second wife, Frances Glandney, a successful interior designer. But today he is in New York publicising Gasms. His hair is jet black, his eyes golden-green, his skin taut, his teeth Alpine white. The look might not be 100% natural, but it works. Even if he allowed his hair to grey, his teeth to yellow and his skin to sag, Robinson would be youthful – possibly more so. The voice, the energy, the enthusiasm and the smarts all make him young.

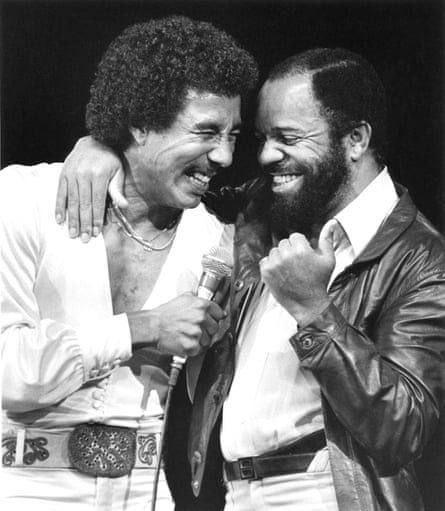

It’s impossible to overstate Robinson’s influence on soul music. He was part of the team at the launch of Motown (then Tamla Records) in 1959, with his great friend Berry Gordy, the founder of the Detroit label. Motown’s first No 1 on the Billboard Hot 100, Mary Wells’s My Guy, in 1964, was written and produced by Robinson. He has written numerous hits for other artists – The Way You Do (the Things You Do), Since I Lost My Baby, Get Ready and My Girl for the Temptations, Ain’t That Peculiar for Marvin Gaye, Don’t Mess With Bill for the Marvelettes, to name a few. Then there are the classics with his group the Miracles, including The Tears of a Clown (written with Stevie Wonder and Hank Cosby), The Tracks of My Tears (written with Warren Moore and Marvin Tarplin), I Second That Emotion (written with Al Cleveland). And the solo hits, such as Cruisin’ and Being With You. He is said to have written more than 4,000 songs. Oh yes, and he was vice-president of Motown.

Nobody wrote about love and desire like Robinson. You’ve Really Got a Hold on Me has one of music’s greatest first lines (“I don’t like you, but I love you”), while the lyrics to The Tears of a Clown (“Now if I appear to be carefree / It’s only to camouflage my sadness / And honey to shield my pride I try / To cover this hurt with a show of gladness”) show why Bob Dylan called him “America’s greatest living poet”.

William Robinson Jr was born in Detroit to working-class parents who had little money but plenty of love. His two sisters were born to the same mother, but different fathers. Although his parents divorced when he was three, they remained united as parents. “My mom used to say: ‘You’re going to have to take care of him after I’m gone, so you love him.’ I don’t know how she knew that. And my dad would say: ‘You gotta love your mom because she’s a great woman.’ Even though they couldn’t stay in the same room for five minutes together, they still promoted each other to me.”

By the age of four, his Uncle Claude had nicknamed him Smokey Joe. “If you asked me what my name was, I’d say Smokey Joe because I’m a cowboy. Even my teachers called me it.” Smokey Joe stuck till the Joe became surplus. When he was 10, his mother died. His older sister, Geraldine, and her husband, who had 10 children, moved into the family home and looked after him as if he was No 11, while his father lived upstairs. He was a bright, conscientious boy who planned to study dentistry until he discovered you had to dissect animals. That didn’t appeal, so he changed to electrical engineering.

His real dream was to become a singer. But, back then, he believed people from his background didn’t do that kind of thing.

A couple of blocks away lived Aretha Franklin and her brother Cecil, another of his closest friends. When Robinson was 10, Diana Ross moved into his street with her family. He says his childhood was wonderful. “It’s beautiful to know we were kids playing together. And these people are some of the most famous people in the world now. We had such joy. I grew up in the hood, baby. And I mean the hood.” Franklin had a more privileged background. “Right in the middle of the ghetto there were two plush blocks, Boston Boulevard and Arden Park, that had lawns and big homes. Aretha lived on Boston Boulevard ’cos her father had money – he was one of the biggest preachers in the country. But it wasn’t like they were the rich kids. No, we just all played together. We stayed lifelong friends.”

They had singing competitions on the Franklins’ back porch, which Aretha and her sister Erma invariably won: “Erma was a helluva singer, too.” Most of his friends from then have died, too many when they were young – through drugs or violence. “When Aretha passed, in 2018, she was my longest friend I had who was still alive. I’d known Aretha since I was eight.”

One day, young Robinson went with his band, the Miracles, to see the managers of his hero, Jackie Wilson. They told him the band didn’t have a chance because he sang high, as did the Miracles’ female singer (Claudette Rogers, Robinson’s girlfriend, who went on to be his first wife and the mother of two of his three children), so their sound was too similar to that of the Platters, the world’s most popular band at the time, who also had a female singer and a male singer who sang high. But Berry Gordy happened to be there and he liked what he heard. He started to mentor Robinson and the Miracles, and they recorded a single, Got a Job.

Robinson started college. One day in class, he was listening to his radio when their single came on. “I went apeshit. I jumped up and ran out of class, and that was it for me. I said to Dad: ‘I want to quit college and try music,’ and he surprised me. He said: ‘You’re only 17 years old – you’ve got time to fail. If it doesn’t work out, you can go back to school.’”

Less than two years later, Motown was formed. “Berry sat us down and said: ‘I’m going to start my own record company. I’ve borrowed $800 from my family. We’re not going to just make black music – we’re going to make music for the world. We’re going to have great beats and great stories.’ As far as I’m concerned, there had never been anything like Motown before that time, and there will never, ever be anything like Motown again.” He’s got a point.

By the age of 19, he and Claudette were married. They remained so for 27 years, although he had affairs along the way. Were he and Franklin an item at one point? “No, just friends.” He smiles. “I do admit when I was about 15 I had a crush on her.” Who wouldn’t, I say. “Hehehe! Yeah, she was fine!” Did he and Ross have a thing? He pauses. “Yes, we did.” How long for? “About a year. I was married at the time. We were working together and it just happened. But it was beautiful. She’s a beautiful lady, and I love her right till today. She’s one of my closest people. She was young and trying to get her career together. I was trying to help her. I brought her to Motown, in fact. I wasn’t going after her and she wasn’t going after me. It just happened.”

What happened to them? “After we’d been seeing each other for a while, Diana said to me she couldn’t do that because she knew Claudette, and she knew I still loved my wife. And I did. I loved my wife very much.”

He looks at me and says this is what he was talking about earlier – understanding love. “You asked me what happened when we get older, and we get wisdom in life. I learned that we are capable of loving more than one person at the same time. And it has been made taboo by us. By people. It’s not because one person isn’t worthy or they don’t live up to what you expect – it has to do with feelings. If we could control love, nobody would love anybody. Nobody would take that chance. Why would you put your heart out there for somebody to be able to hurt you like that and make you able to have those feelings?”

I ask if he has heard the rumour about him and Ross. There is a story, I say, that you two are the real parents of Michael Jackson. “They say I’m the baby daddy?” His voice rises an octave. “Hehehehe! Hooohooho! They say Diana Ross and I had Michael?” Yes. “Oh my God! I never heard that one, man! That’s pretty good. That’s funny! That’s funny!”

I wonder if she has heard it. “I’m gonna call her and ask her.” He is still laughing. “That’s funny!”

Robinson has examined the complexities of love beautifully in his songs. But his understanding is by no means confined to sexual love. He talks about his love for his father; the brother-in-law who became his second dad; Aretha’s brother Cecil, who died at 50; Sam Cooke, who was 33; and Marvin Gaye, who was killed in 1984 by his father, aged 44. “I do miss them. I wonder what they would have been like were they alive today. Especially Marvin, man. Marvin and I were brothers, man. We hung out almost every day of our lives. To lose him at that age was a real blow … The last thing I ever expected to see him was dead.” And such a violent death? “Yes, exactly. He’d got into trouble with drugs when he died.”

Robinson also succumbed to addiction. Was he in trouble when Gaye was? “It was during and afterwards. My most dramatic bout with it was afterwards. During, we did it together. I just never got strung out. I was never a cocaine person then. I got involved with that after he died. And it took me out. It was the worst time of my life – a life experience I will never forget, but I will never do again.”

Had he been as close to Gaye as to Gordy? “No, I’m not as close to any man on Earth as I am to Berry. Berry is still my best friend. It was another kind of relationship. It was different because Berry’s never done drugs. Marvin and I had a different relationship – we were promiscuous, the same age. With Berry, you didn’t take any drugs around him. We all respected him. He was our leader, our boss. He just happened to be my best friend, too.

“Berry calls it a bromance,” he says. “We have a love for each other, man; we’re there for each other. When I was going through my heaviest part with the drugs, for two years I was damn near dead. It wiped me out. But Berry, man, during that time he’d bring me up to his house and lock me up there for a week or two. He’d just keep me there so I couldn’t keep doing what I was doing to myself. He looked after me.”

Robinson tells me that one night he walked into a church, met the minister and told her everything. He went in an addict and came out free from drugs. It was a miracle, he says. “That was May 1986 and I’ve never touched drugs since.”

One of his greatest Motown memories is Martin Luther King’s visit. “You know what he said to us? He said: ‘I want to do my “I have a dream” speech on Motown because you guys are doing with music what I’m trying to do politically – bring people together. You have united the races and the world with music.’”

In their earliest days, Robinson says, Motown’s acts played to segregated audiences – black kids on one side, white kids on the other. “We went back a year later and they were all dancing together. White boys had black girlfriends, black boys had white girlfriends, and it was all because of the music. We gave them a common love. So I’m really, really, really, really, really proud of that. About a year after we started Motown, we started getting letters from white kids in those areas: ‘Hey, man, we got your music, we luuurv your music, but our parents don’t know we have it because if they knew we had it they might make us throw it away.’ A year or so later, we got letters from the parents. ‘Hey, we found out our kids were listening to your music. We were curious, so we started listening to it. We luuurv your music. We’re glad the kids have it.’” He tells the story with such vim, but he looks emotional. “I’m so proud we started to break down barriers.”

Does he ever look back and wish he had become a dentist? He laughs. “No! I also had aspirations of playing baseball. I think about that all the time. I think I could have been the greatest player in the history of baseball and my career would have been over 50 years ago. If I’d been the greatest dentist in the world I’d have been retired for 20 years by now! But I was blessed enough to be in music, which gives you longevity if you love it, if you respect it.”

It’s all about keeping perspective, he says. “You’ve got to understand you didn’t start it and you ain’t gonna finish it and you don’t go getting a big head ’cos you’ve got a record out or people recognise you: ‘Oh, boy, I’m hot shit.’ ’Cos you’re not: you’re just a person who’s blessed enough to have your dream of being in showbusiness come true. I tell young people all the time: ‘Don’t go getting hoity-toity ’cos you’ve got a hit record, because this started way, way, way before your great-grandmother was born and it’s going to go on way, way, way after you. So you better know that!’”

Was there any danger of him getting hoity-toity? “No, I had a better upbringing than that. I was always taught that I’m human and that’s the best you can be. You don’t get no bigger than that on our planet.”

I ask a final question. What is his favourite gasm? “I guess if you’re gonna start at the world, you’d have to say God is my favourite gasm, but other than that, love is my favourite gasm. I wish love on the world.” And with that, the global minister for love leaves me brimming with the stuff.

Gasms is released on 28 April. For more information, go to smokeyrobinson.com

[ad_2]

#feel #sexual #Smokey #Robinson #love #joy #drugs #Motown #affair #Diana #Ross

( With inputs from : www.theguardian.com )